Not many sports-minded African Americans were surprised when Brian Flores filed a racial discrimination suit against the NFL. That’s because the numbers are irrefutable: Approximately 70% of NFL players are Black, while only three head coaches of 32 NFL teams, just under 10%, are Black.

The relevant numbers in the NBA reveal an important difference between these two organizations: Black players make up 74% of the NBA's rosters while 14 of the 30 teams, 47%, are led by Black head coaches.

Yet up until the early 1950s, the system in effect mostly limited Baltimore Ravens JerseyBlack players to playing defense, rebounding, setting picks and passing to white players, who did most of the scoring. A notable exception was Ray Felix from Long Island University, who averaged 17.6 points for the Baltimore Bullets as a rookie in the 1953-54 season.

What should Elon Musk do?:He should take over Twitter, shut it down and fire the social media giant into space

In addition, there was a quota system in effect that limited the number of African American players each team could have.

This limitation gradually increased until Dec. 26, 1964, when Red Auerbach’s Boston Celtics fielded an all-Black starting five – Bill Russell, Tom “Satch” Sanders, KC and Sam Jones plus Willie Naulls, who replaced the injured Tommy Heinsohn.

Story from Biogen

Hope for treating spinal muscular atrophy

See More →

A difference in two players

Even so, the difference between how the NFL and the NBA have handled racial situations is best exemplified by how two specific players were treated.

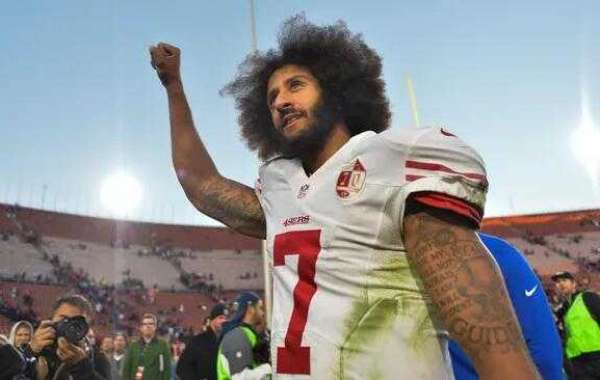

Colin Kaepernick was an accomplished quarterback who led the San Francisco 49ers to the Super Bowl in 2013. Throughout the 2016 season, however, Kaepernick chose San Francisco 49ers Jerseyto protest the racial injustice, police brutality and systemic oppression in America by kneeling during the pregame playing of the national anthem. As a result, he was blackballed by every club in the league.

Colin Kaepernick led the San Francisco 49ers to the 2013 Super Bowl.

Compare this with what happened to Chris Jackson, a high-scoring guard for the Denver Nuggets (averaging as much as 19.2 points in each of two seasons), who converted to Islam in the early 1990s and changed his name to Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. Abdul-Rauf's beliefs forbade him from taking part in any ceremony that honored nationalism, oppression or tyranny. As a Black man, he believed that the national anthem fulfilled all of these definitions, so he sat during the playing of our national anthem, and when he did, he was suspended.

Get the Opinion newsletter in your inbox.

What do you think? Shape your opinion with a digest of takes on current events.

Delivery: Daily

Your Email

ALL-AMERICAN STORY:In Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, Black female strength tells an all-American story

His banishment lasted only one game, after which Abdul-Rauf took to staying in the locker room while “The Star-Bangled Banner” was played. Then, after consulting with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, he stood with his teammates, bowed his head and softly said an Islamic prayer. Abdul-Rauf went on to play several more seasons in the NBA.

Denver Nuggets guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf in 1995.

'SPEAK YOUR TRUTH': Former NFL assistant coach Eugene Chung supports Brian Flores

Notice the difference between how America’s most popular sport,New York Giants Jerseyprofessional football, treated Kaepernick, who was punished by being banished from the league, and how the NBA treated Abdul-Rauf.

Finding a better way

In the NBA, a way was found for Abdul-Rauf to act in accordance with his beliefs and still continue to play.

There’s no question that the NBA’s approach to racial discrimination is far ahead of the NFL’s. Indeed, the progression of racial opportunities in the NBA is likewise more advanced than the commercial and social opportunities for African Americans throughout our national culture.

In so many meaningful ways, then, the legacy of the NBA's actions is much more important than wins, losses and even championships won.